Survivors of abuse can be prone to extreme ‘flight or fight’ responses

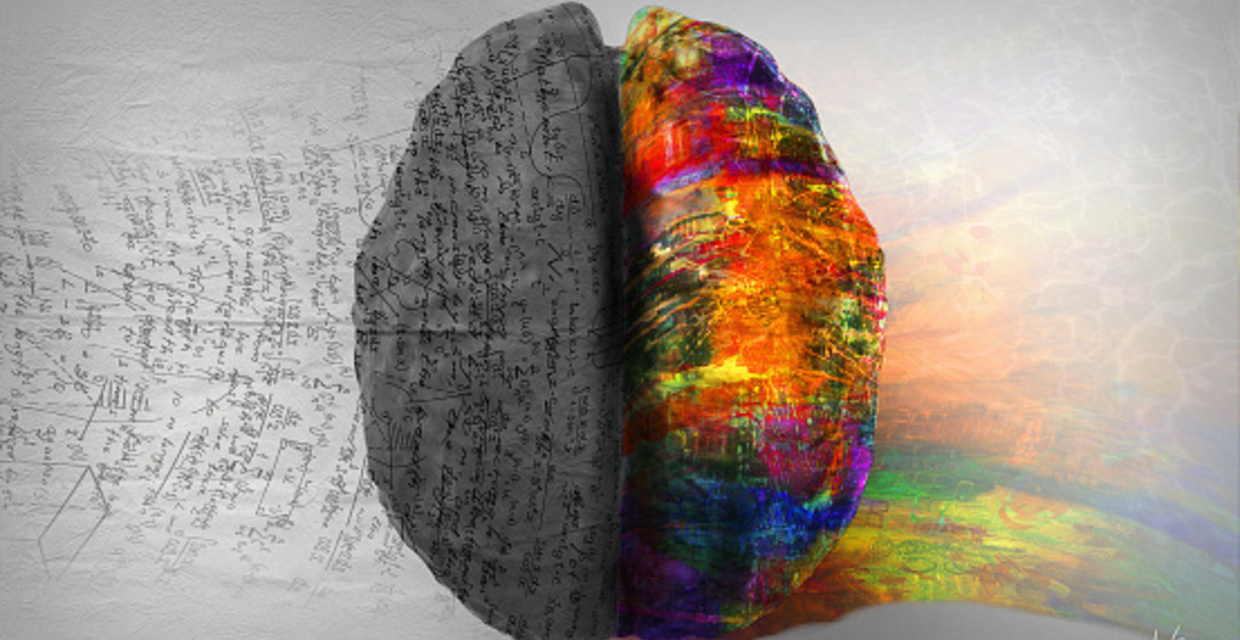

Our brains are mysterious and complex organs, made up of billions of neurons. They control virtually everything we do, from breathing to blinking. And, our brains are ever changing. Each new memory or thought creates a new connection in the brain, in essence, rewiring it.

For individuals who continually experience traumatic events, or who relive traumatic memories from their childhood as adults, this means the brain can rewire itself in such a way that sometimes causes us to feel overly stressed, even when there’s nothing overt to stress about. Psychological Associate Kimberley Shilson told New York University’s The Trauma and Mental Health Report that, when trauma occurs repeatedly, cortisol—the hormone released during times of stress—can exist in abundance in the brain. This hormone can activate a part of the brain called the amygdala, the area responsible for emotions, emotional behavior and motivation, and cause even more cortisol to be released.

“The amygdala of traumatized individuals is often overly sensitive, resulting in extreme alertness. These individuals may appear aggressive, as they might be overly sensitive to perceived threats (words or gestures from peers), or withdrawn due to fear of being close to others,” says Shilson. “It is a self-perpetuating cycle that leaves the individual with heightened sympathetic arousal (‘fight or flight’ response).”

Licensed Psychologist and Childhood Domestic Violence Victim Advocate,Linda Olson Psy.D, agrees with this assessment. She works with childhood domestic violence (CDV) survivors and adult survivors of

The increased cortisol alerts the brain to threats that may not even be there because, says Olson “you’re always believing and therefore reacting as if they are.”

Changing Your Brain

Just as trauma can rewire one’s brain in a negative way, the proper therapies can rewire it back. Tells Shilson in the Report, “Neuroplasticity refers to the brain’s ability to reorganize itself through new connections and brain growth. Awareness of this potential provides a sense of hope to individuals suffering from [trauma] as well as their treatment providers. Treatment that considers the brain’s neuroplasticity can, in a sense, reverse the effects of trauma.”

What does that mean, exactly? Basically, says Olson, “the only way we can feel better is to befriend what is going on inside of ourselves in terms of emotional regulation. Resolving traumatic stress means restoring a proper balance between the rational and emotional brain, so that you can feel in charge of how you respond and how you conduct your life. When we’re triggered into states of hyper- or hypo-arousal, we are pushed outside our ‘window of tolerance.’ We become reactive and disorganized, our filters stop working, sounds and lights bother us, unwanted images from the past intrude and we panic or fly into rages,” says Olson.

Self-awareness of one’s triggers that send a person into a flight or fight response is the first step. But this often means revisiting traumatic memories in order to confront them head-on. This can be difficult for many survivors. But if that hurdle can be crossed through trauma-informed treatments, says Olson, a survivor can rewire the brain to have a new, non-traumatic response.

Say a survivor is triggered by the sound of heavy footsteps coming down a hallway. In their memory, this sound indicated that their abuser was home and that some type of abuse was about to occur. Hearing footsteps now makes the survivor’s heart race. His or her hands begin to sweat and they begin to panic. Or, the survivor readies him or herself to fight whoever is coming their way.

Therapists like Olson may use evidence-based treatments such as a mindfulness-based cognitive behavior therapy, dialectical behavior therapy or EMDR to help a patient learn how to regulate these negative emotions and rewire the brain to have a new experience in relation to the trigger.

“The end goal is to reduce or eliminate living in a constant state of fear, uncertainty, doubt or hypo-arousal by changing the negative core beliefs internalized in childhood.”

Righting the Wrongs in Childhood

Abuse is a learned behavior, says Olson. “The single best predictor of becoming a perpetrator or victim later in life is whether or not one grows up living with it”.

A child’s brain is far more susceptible to long-term negative effects of witnessing or experiencing abuse since the young brain isn’t even fully developed until closer to age 25.

“The saddest, most tragic part is that we don’t often shine a light on CDV. There are more kids in domestic violence shelters, by and large, than parents. What happens is we start by overlooking the impact, then minimizing and denying it, and it reinforces the denial and shame that the child will internalize.” Later on in life, says Olson, this shame can manifest as depression and anxiety, “and these individuals don’t even know why they feel that way. They’re not able to connect the dots.”

“By raising awareness, we heal the shame and isolation that prevents many from finding the help they need.”

For more information on CDV, read “ Why You Can’t Just ‘Get Over’ the Adversity You Faced in Childhood.”