Here, a survivor gives us a look inside our state’s dark world of sexual exploitation and forced labor.

“I thought at one point I was dead, and I went to hell. … I would wake up, and [my traffickers] would put an IV in me. I never, ever shot myself up. I didn’t know how to, so they would give me drugs, literally, and keep me inebriated… and then, of course, they would immediately start finding people to buy me. That was pretty normal,” says Kate*, who, at nearly 18 years old, was trafficked for 1.5 years.

Human trafficking is a broad term to define modern-day slavery, and victims can be used for sexual exploitation, forced labor, involuntary criminal acts and even the harvesting of their organs. It’s an underreported crime that often goes unnoticed, carries multiple misconceptions, and, when you dig deep, unearths corruption.

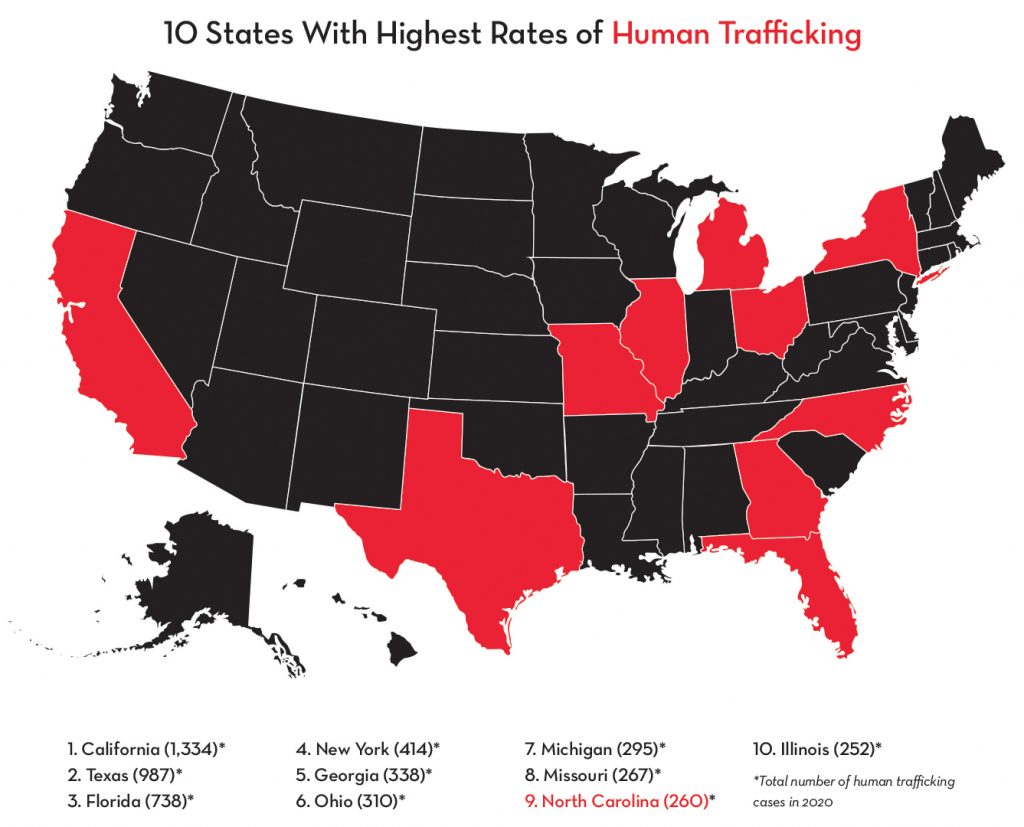

While every state reeks of cases, according to the National Human Trafficking Hotline (which released its annual report for 2020 in late 2021), 260 cases were reported in North Carolina in 2020 alone—ranking our state as 9th in the U.S. for human trafficking, with the majority of victims being adult women.

For Kate, life took a sharp turn her senior year of high school. She was raped, and as a coping mechanism, she turned to alcohol and marijuana. Soon thereafter, she dropped out of school and began living on her own.

A friend’s mom introduced her to the man who became her trafficker, who lured her into his car with the promise of drugs and safety from a storm that was wreaking havoc on the area. After being driven just three hours from home, Kate fell victim to sexual exploitation.

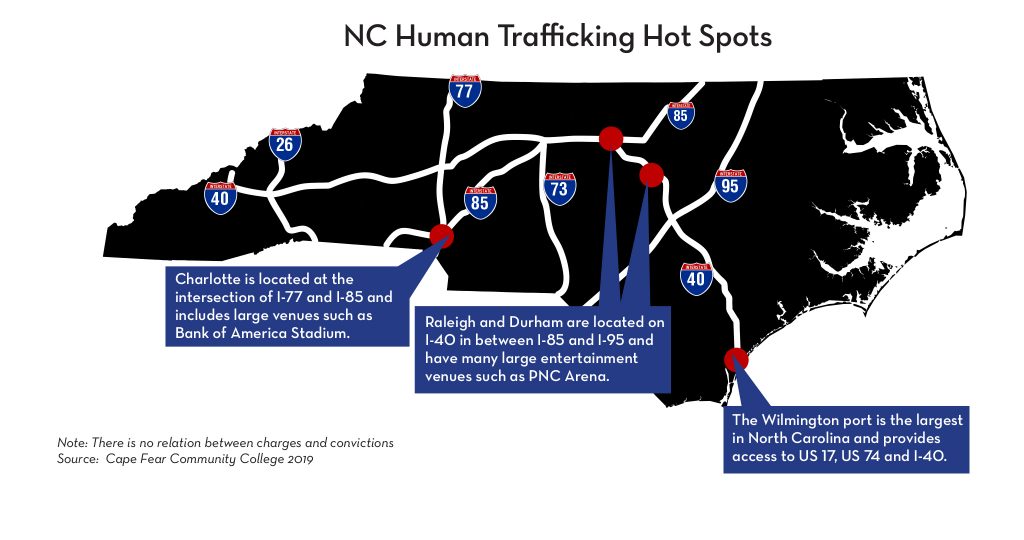

While it’s often thought that a person must be transported across a border for it to be considered trafficking, many victims are trafficked in or close to their hometowns, according to the North Carolina Department of Administration.

For Kate, when she wasn’t being sold, she was mostly locked and monitored in different traffickers’ homes—sometimes with other victims—and only given access to a toilet, water and drugs, including heroin and fentanyl, which her traffickers used as a form of control.

“I was probably 95 pounds when I got saved,” she says. “I would steal Snickers bars and drinks. They wouldn’t give you food. They would take all the money that you earned. … If I wanted underwear, I would have to go into Walmart or the thrift shop and steal it.”

Fear of being arrested for crimes committed is one of several reasons victims might not try to escape and report their trafficker, according to Nicole Bernard, chair of the North Carolina Coalition Against Human Trafficking. Additionally, the victim might fear retaliation, be in a relationship with their trafficker or have clients in law enforcement.

Kate, however, tried to escape.

“I was actually on one of the military bases, and I ran away—because one of my traffickers was in the military,” she says. “I remember sitting in a pool of water and then hiding in a garbage can beside a gas station. I hid there for, who knows, probably a day, and they ended up pulling me up and pointing a gun at me and telling me to get in the car.”

Kate’s freedom came later, when her traffickers were pulled over by state troopers for having an expired license plate, and after asking if they could speak with her outside the car, she agreed.

“Some of the people that ended up raping me were police officers and military officials, so seeing him, and him asking me to get out of the car, I was like, ‘Oh, not this again,’ so I didn’t really know what to expect,” she says. “But when I got into his car, he just gave me the whole spiel. He was like, ‘We’re going to get you into rehab. We’re going to get you therapy. We’re going to get you back to your parents.’ And for some reason, I don’t know why—honestly, I like to think of it as God—I believed him.”

After being rescued, Kate spent approximately two years in recovery programs for those who’ve experienced human trafficking. For a time, she moved in with her parents, but after struggling with her addiction, she returned to therapy for six months.

As for her trafficker, Kate says he spent four years in and out of jail before their case went to trial, as he was released on a $1 million bond and later arrested for trafficking another victim. Once tried, however, he was sentenced to 40 years to life in prison—and he still has to go to trial for other victims he has trafficked as well.

“(For a week), I was there testifying from 6am to 6pm with him just brutally harassing me and saying things and threatening me,” says Kate. “It paid off, but that is not for everybody. … If I was someone else who didn’t have the courage, it would definitely be easy to not testify, to not press charges, and, therefore, that trafficker would be out on the street right again.”

In North Carolina, multiple laws have been passed to help prevent human trafficking, protect victims and penalize traffickers. The Safe Harbor Law, created in 2013, laid the foundation by creating a “safe harbor” for victims of human trafficking and prostituted minors.

“I think what advocates were really excited about was that this was going to make a significant dent in the crime, and it was a start, but if you go back and look at the data, there were very few prosecutions,” says Bernard. “I think that’s because if you don’t have the services for survivors, they’re not going to disclose, and they’re not going to want to prosecute and participate as a witness.”

The Safe Harbor Law, however, is responsible for modifying the membership of the North Carolina Human Trafficking Commission, which, among other things, makes recommendations to the General Assembly on ways to eradicate human trafficking and administers funds to organizations working to address the issue.

Plus, the NC Council for Women & Youth Involvement, an agency within the state’s Department of Administration, advises the governor, legislature and state departments on issues that impact women and youth, including human trafficking.

At the nonprofit level, Bernard says over 100 organizations across the state are working to help survivors and eradicate human trafficking. One example is Shield NC, founded by Bernard, which works to influence policy; support the restoration of victims; and educate groups, such as medical professionals and hotel staff, on ways to identify and appropriately respond to victims.

Today, Kate is working, going to school for pre-med; raising a child; and involved in several nonprofits aimed at combatting human trafficking, including the Survivors’ Network, a branch of the North Carolina Coalition Against Human Trafficking initiated in September 2021 that’s led by survivors. The network empowers survivors to use their lived experience to become leaders in the antitrafficking movement by providing them with opportunities for personal and professional development, as well as growing their advocacy skills.

After going through an application process, survivor-leaders take part in a peer support group launched in January that meets virtually once a month for 12 months. Taught by the network’s director and co-founder Latiana Appleberry, members focus on topics such as interpersonal skills, boundary- and goal-setting, finances, budgeting, anger management, self-care, and more. The New Dream Fellowship Fund, once up and running, will also allow members to take part in professional development classes, seminars and conferences not offered by the network.

Once involved with the support group and garnering five additional hours of required training, survivor-leaders are eligible to be part of the network’s Speakers’ Bureau, which connects them with agencies, such as law enforcement and allied health professionals, looking for survivors to advise, consult and speak on the subject.

To honor survivors and raise money for the New Dream Fellowship Fund, the Survivors’ Network is hosting its first annual gala called A Night in Bloom at the Raleigh Country Club on June 25. Proceeds will go toward advancing the Speakers’ Bureau and growing and sustaining the peer support group.

When asked to help name the event to best reflect their experiences, survivors chose A Night in Bloom. “They see themselves like wildflowers,” says Bernard. “They may have been scattered from the garden with its perfect rows, but they were able to thrive in the harshest of conditions, and there was beauty in that.”

Content retrieved from: https://raleighmag.com/2022/05/modern-day-slavery/.